True to its nomadic spirit, Rajasthani folk music is seducing new audiences through international collaborations and music festivals like the Jodhpur RIFF.

Folk music hits all the high notes as it finds fertile opportunities in and outside of the desert region.

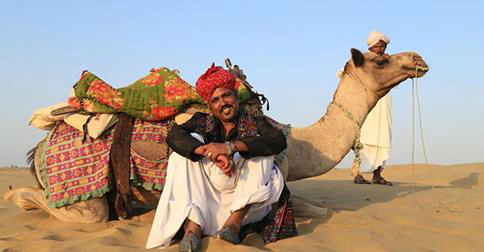

Amidst a landscape of muted greys and browns from the dust that never seems to settle in the Thar Desert are fragments of the brightest colours. Here, in Rajasthan, locals create the vitality lacking in the ruins around them, not only through their colorful attire, but also through the artistically rich music that resonates over the sand dunes. Music in Rajasthan paints daily life, knitting people together through songs for every occasion. Whether it be a hymn sung along the way to collect water, or strumming strings to greet the morning or the arrival of a new baby, song emerges rhythmically, naturally, for the people of Rajasthan.

Amidst a landscape of muted greys and browns from the dust that never seems to settle in the Thar Desert are fragments of the brightest colours. Here, in Rajasthan, locals create the vitality lacking in the ruins around them, not only through their colorful attire, but also through the artistically rich music that resonates over the sand dunes. Music in Rajasthan paints daily life, knitting people together through songs for every occasion. Whether it be a hymn sung along the way to collect water, or strumming strings to greet the morning or the arrival of a new baby, song emerges rhythmically, naturally, for the people of Rajasthan.

The districts of Barmer and Jaisalmer, regions in western Rajasthan and in the heart of the Thar Desert, contain many small villages with distinct castes and tribes including the Langas and Manganiyars who are multi-generational families of skilled musicians. Originating in the Sindh region of Pakistan and descendants of Rajputs, these tribes travelled across the Thar and settled in the villages of Rajasthan bringing with them a large repertoire of music with rich and varying sounds. Incorporating both Islamic and Hindu traditions, the result was a musical form that appealed to the powerful rulers of this vast region who became their biggest patrons, allowing these musicians to earn a livelihood and pass on their art of storytelling from one generation to the next. Typically, the Langas (meaning ‘song givers’) who converted from Hinduism to Islam in the 17th century found patrons amongst the Yajman who were cattle breeders, farmers and landowners. Manganiyar meaning ‘those who ask for alms’ would visit the homes of their patrons, consisting of the Hindu Rajputs and Sindhi Muslims, to sing appropriate songs, and in turn, would be rewarded. The songs of the Langas and Manganiyars praise their daily life as lyrics draw upon the landscape, customs, chores, historical rulers, and the glory of the gods to bring joy to the people as they move about their daily activities.

Raw, throaty vocals depicting stories of love and war are often accompanied by instruments that produce the trademark gypsy music of the desert. The knowledge of these instruments is usually not due to any formal training, but rather learned by exposure and experience through storytelling, dance, and performance. The kamaicha, made of mango wood, fourteen steel strings and three strings of goat’s intestine is played with a horse-haired bow. Being one of the oldest instruments in the world, it was made popular by the late Rajasthani folk musician Sakar Khan (1938-2013) and now included in the ethnomusicology archives of Smithsonian Folkways, the nonprofit record label of the Smithsonian Institution, the national museum of the United States. The dholak is a hollow barrel shaped drum with a simple membrane on the right hand side and lined with tar, clay or sand on the opposite side to produce a lower pitch. Khartaals (‘khar’ meaning hand and ‘taal’ for rhythm) are pairs of small hand-held wooden blocks to produce a clapping sound. The Sindhi sarangi (made of 4 main plus 20 sympathetic strings) is a bowed instrument widely used by the Langas and can produce a tone closely resembling the human voice. Master sarangi musician, Lakha Khan, 67, fears that Rajasthani folk music is in danger of becoming a dying art as youth gravitate towards easier instruments like the harmonium, disconnecting them from ancestral roots.

Raw, throaty vocals depicting stories of love and war are often accompanied by instruments that produce the trademark gypsy music of the desert. The knowledge of these instruments is usually not due to any formal training, but rather learned by exposure and experience through storytelling, dance, and performance. The kamaicha, made of mango wood, fourteen steel strings and three strings of goat’s intestine is played with a horse-haired bow. Being one of the oldest instruments in the world, it was made popular by the late Rajasthani folk musician Sakar Khan (1938-2013) and now included in the ethnomusicology archives of Smithsonian Folkways, the nonprofit record label of the Smithsonian Institution, the national museum of the United States. The dholak is a hollow barrel shaped drum with a simple membrane on the right hand side and lined with tar, clay or sand on the opposite side to produce a lower pitch. Khartaals (‘khar’ meaning hand and ‘taal’ for rhythm) are pairs of small hand-held wooden blocks to produce a clapping sound. The Sindhi sarangi (made of 4 main plus 20 sympathetic strings) is a bowed instrument widely used by the Langas and can produce a tone closely resembling the human voice. Master sarangi musician, Lakha Khan, 67, fears that Rajasthani folk music is in danger of becoming a dying art as youth gravitate towards easier instruments like the harmonium, disconnecting them from ancestral roots.

Music is not simply a past-time for those in Rajasthan, but their livelihood too. It is said that the babies of the musical families sing even before they learn to talk. From a tender age they learn the rhythms and sounds that make up the life around them. Small groups of children are often seen in the desert singing and playing music amongst themselves, preparing for their lives as performers. The relationship between the community and music is integral to the Rajasthani culture. No festival, ritual, celebration, or act of mourning begins without music, thus creating a reliance on song. Similarly, the music cannot exist without the community that gives it occasion for these songs. This makes performers integral to the culture, so it is hardly surprising that many Rajasthanis earn a living thorough the arts.

As society, especially the younger generation, is lured by a more urban, western lifestyle there is fear that the ancestral music of the Langas and Manganiyars will be lost. As a result, there have been initiatives to promote Rajasthani folk music within India and internationally. Alongside the rise of the electronic music scene in India, folk music is enjoying its period to shine through festivals such as Jodhpur RIFF (formerly known as Rajasthan International Folk Festival) –‘riff’ refers to a short repeated phrase, frequently played over changing chords or harmonies– an annual five-day festival set in the blue city of Jodhpur with the sprawling Mehrangarh Fort as the setting for dusk-to-dawn performances between local Rajasthani folk musicians and international artists. Here, borders become irrelevant as east meets west and the only language that matters is music. The festival was founded by the Jaipur Virasat Foundation and Mehrangarh Museum Trust, under the local patronage of the titular Maharaja Gaj Singh of Marwar-Jodhpur and international support of Mick Jagger.

As society, especially the younger generation, is lured by a more urban, western lifestyle there is fear that the ancestral music of the Langas and Manganiyars will be lost. As a result, there have been initiatives to promote Rajasthani folk music within India and internationally. Alongside the rise of the electronic music scene in India, folk music is enjoying its period to shine through festivals such as Jodhpur RIFF (formerly known as Rajasthan International Folk Festival) –‘riff’ refers to a short repeated phrase, frequently played over changing chords or harmonies– an annual five-day festival set in the blue city of Jodhpur with the sprawling Mehrangarh Fort as the setting for dusk-to-dawn performances between local Rajasthani folk musicians and international artists. Here, borders become irrelevant as east meets west and the only language that matters is music. The festival was founded by the Jaipur Virasat Foundation and Mehrangarh Museum Trust, under the local patronage of the titular Maharaja Gaj Singh of Marwar-Jodhpur and international support of Mick Jagger.

Rajasthan’s musicians are now being wooed by Bollywood and travelling to international festivals marking the beginning of a period in which Rajasthani folk music will finally get the global platform it deserves to shine beyond the appreciation of loyal patrons and curious tourists. We spoke to Mame Khan, a well-respected local musician who has performed across the globe and nationally on MTV India’s Coke Studio stage. Further, he was the lead vocal of ‘The Manganiyar Seduction’ by Roysten Able, a travelling theatrical production inspired by the red light district of Amsterdam. “Over there [Amsterdam] it’s a seduction of the body. Over here [Rajasthan] it’s a seduction of the soul,” explains Able about his show. Khan has also lent his voice to popular Bollywood movies and is currently preparing to release his first solo album. So true to its gypsy roots, Rajasthani music is travelling and taking on new exhilarating forms.

Rajasthan’s musicians are now being wooed by Bollywood and travelling to international festivals marking the beginning of a period in which Rajasthani folk music will finally get the global platform it deserves to shine beyond the appreciation of loyal patrons and curious tourists. We spoke to Mame Khan, a well-respected local musician who has performed across the globe and nationally on MTV India’s Coke Studio stage. Further, he was the lead vocal of ‘The Manganiyar Seduction’ by Roysten Able, a travelling theatrical production inspired by the red light district of Amsterdam. “Over there [Amsterdam] it’s a seduction of the body. Over here [Rajasthan] it’s a seduction of the soul,” explains Able about his show. Khan has also lent his voice to popular Bollywood movies and is currently preparing to release his first solo album. So true to its gypsy roots, Rajasthani music is travelling and taking on new exhilarating forms.

Did you always know you would be a musician?

MK: I was born and raised in a small town called Satto in Rajasthan, near Jaisalmer, the golden city. I actually belong to a family of musicians that spans 15 generations in the oral tradition. My musical journey began during my childhood. My late father and teacher, Ustad Rana Khan – who was a legendary singer – has always inspired me. So, since the beginning, it was quite clear for me that my life would be all about music. Yet, I had no idea where this would take me.

Who has been your biggest influence?

MK: My father and his compositions continue to inspire me every day. In his memory I travel around the globe and try to keep our beautiful family tradition alive. But beyond his influence, it is the pure beauty of our Rajasthani folk and sufi music that inspires me so much to keep playing it day to day. There is magic in the old words and melodies.

Do you think folk music is a dying art amongst the Rajasthani youth?

MK: The Manganiyars look back to more than 15 generations of musical history. Our oral tradition has been passed on from one generation to the next so music is an integral part of our life and community structure. Thinking about the future of our community and music gives me mixed feelings. Change is needed and a lot of things in Rajasthan have changed already, but at the same time we need to retain our old musical traditions. Keeping traditions is not easy in a fast changing world. We have to find new ways to keep our music alive. We have to invent ways of learning in order to keep our treasure.

One thing keeps me very positive: whenever I play a concert in any part of the world, the audience cannot get enough of our music! We get a lot of appreciation and respect for our music all around the world, and we do get the same in India. At the same time I see massive potential and need, let it be from the private sector or from the government side, in order to protect cultural heritage and especially intangible art in India.

The instruments of Rajasthan are very unique – is there an interest by the young people to go into careers as craftsmen?

MK: Sadly I must say that day by day less people know how to build our instruments. To work as a regular carpenter seems to many people much more promising. As of now. I know about a few initiatives to encourage the local community to keep building these instruments and to keep the craft alive. In my concerts, I always try to highlight our local instruments, so that people get to know about them and hopefully keep asking for them in the future.

What do you think of music festivals such as Jodhpur RIFF that fuse east and west to create a new sound?

MK: I think these kind of initiatives are a great opportunity for Indian artists to explore new ways and to widen their networks. Anything new is welcome, as long as one masters and does not forget about the original art form.

If you had a wish for the music scene in Rajasthan to flourish even further, what would that wish be?

MK: I think our chance is the next generation. See, education is the key to a lot of things and at the same time the children of our community need to practise and live their music. What we need is a more inclusive way of quality education which allows and encourages the children to study and to learn their traditional music.

Do you think local Rajasthani musicians are getting the exposure they deserve? If not, what are some obstacles they currently face?

MK: I am grateful for all the chances which exist in order to promote our art and I think there are great initiatives. Yet the potential we have is so much bigger and I see much more scope for us to promote our art. After all, as unromantic as it might sound, music is a tough business. I often feel that great artists who have less connections are having problems reaching out to the people.

Some Rajasthani artists like yourself have had the chance to perform on MTV India’s popular Coke Studio stage. Has this helped your career and if so, how?

MK: For sure there was a positive impact, especially my song called ‘Chaudhary’ -by Amit Trivedi- was a great hit, and it reached so many people that even now people keep asking for the song. The mass appeal of such TV events is just so much stronger than a single live show. It was a great opportunity for me!

Do you think Rajasthani musicians are seeking fame quickly nowadays as some artists have begun touring around the world or collaborated with Bollywood filmmakers?

MK: There is quite a handful of popular artists who keep travelling and playing shows. But with the great talent we actually have, these are only a few known faces.

What has been the highlight of your career thus far?

MK: Maybe not a highlight as such but a dream-come-true-concert was a show in Italy, where my father and I had the chance to play together. Since childhood, I had been dreaming to play a show abroad with my father.

What is next for Mame Khan?

MK: Currently, I am working on my first album. It’s going to be something very personal and very special. Keep watching for it on my Facebook page and website.

Story by Bethany Trepanier (with research assistance by Abhi Patnaik) // Mame Khan interviewed by Rupi Sood // All photographs (excluding photo of Mr. Khan) kindly provided by Vaibhav Mehta and Jodhpur RIFF