Swiss architect and designer Pierre Jeanneret’s iconic Chandigarh Chairs, which he designed while working alongside his architect cousin, Le Corbusier, who had been commissioned to build the new city of Chandigarh in post-Independence India, are once again making a splash as they find their way into the homes of celebrities, collectors and trendsetters.

The working methods that I discovered in India finally taught me self-esteem after so many failures in France.

Pierre Jeanneret

Photographs by Rupi Sood at Leclaireur Gallery (Paris, France)

In 1950, three years after independence from British rule and partition from Pakistan—whereby the province of Punjab was divided into two, with the western side containing the capital of Lahore going to Pakistan, and the eastern part to India—the first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, wanted to design a new Punjabi capital, one that would be filled with modernist architecture and design to represent a nation that was innovatively moving into the future. So, he commissioned renowned Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, born as Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (1887-1965), to design Chandigarh (meaning stronghold of the goddess Chandi), which is located 260 kilometres north of New Delhi and serves as the capital city of India’s Haryana and Punjab states.

Once Le Corbusier arrived in India, for what would be his most ambitious project to date, along with British architects, husband-wife duo Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, and his architect cousin Pierre Jeanneret (1896-1967), he planned a grid-like city divided by boulevards and public parks, and designed many of the government’s administrative headquarters such as the three concrete buildings that comprised the Capitol Complex: the High Court, the Palace of Assembly and the Secretariat. He also created the government’s symbol in the form of a 26-metre-high Open Hand steel sculpture as “the hand to give and the hand to take; peace and prosperity, and the unity of mankind” but it was not erected until 1985, twenty years after his death, due to funding problems.

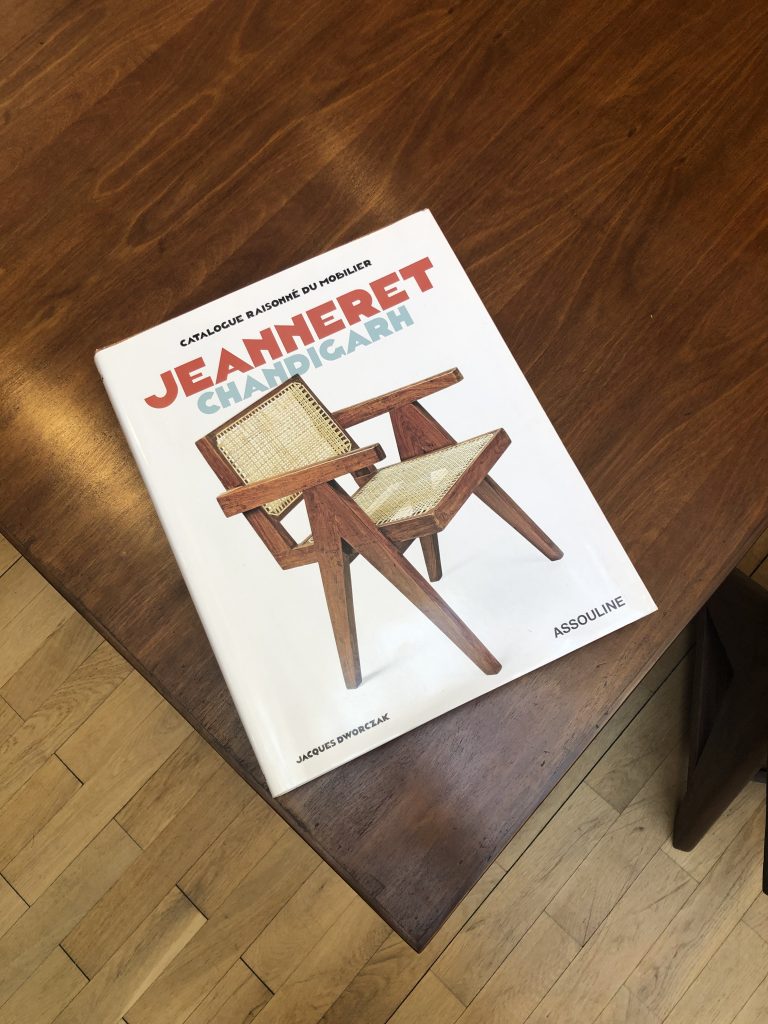

Pierre Jeanneret, on the other hand, took over the responsibility of the mass housing and civic projects and co-designed Panjab University with an Indian team of architects and developers. He also worked with craftsmen to design furniture for these buildings by sourcing readily-available, local materials that could withstand the Indian climate — teak, rosewood and rattan caning. Jeanneret’s elegant, minimalist designs—inspired by the shapes and lines of the new architecture for Chandigarh’s legislative and academic institutions—included variations of benches, tables, cabinets, desks, bookshelves and chairs, including the popular, inverted V-legged style that has now become the chair du jour.

Catalogue Raisonné du Mobilier: Jeanneret Chandigarh by Jacques Dworczak; Published by Assouline (2019) / Photograph by Rupi Sood

Even though the city of Chandigarh was completed in the mid-1950s, and Le Corbusier left half-way through the project, Jeanneret remained working as the city’s Chief Architect until 1965 when he returned to Geneva for health reasons. Upon his death in 1967, as per his request, his cremated ashes were scattered in Lake Sukhna in Chandigarh, the city that allowed him to come out of his famous cousin’s shadow. In the 1980s however, much of the furniture he designed was discarded or stored away due to disrepair from over-usage and results of extreme heat and humidity. To local residents, the furniture did not hold the same symbolic meaning as it did for Jeanneret, who was creating pieces for a new, modern nation as envisioned by Prime Minister Nehru. It was tossed aside on streets and replaced with more sleek styles as consumer tastes evolved and, in fact, much of Jeanneret’s furniture was destroyed in the process, as it was taken apart in junkyards for repurposing as firewood.

Discarded Pierre Jeanneret chairs in Chandigarh / Video still via artist Amie Siegel and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

Beginning in the late 1990s, Parisian antiques dealers and gallerists such as Eric Touchaleaume (Galerie 54), François Laffanour (Galerie Downtown), Philippe Jousse (Jousse Enterprise), and Patrick Seguin (Galerie Patrick Seguin) began purchasing the discarded items to restore and resell at lucrative prices while the citizens and officials of Chandigarh perceived the furniture which fell into disrepair as pure ‘junk’. It was not until years later that they realized the Jeanneret furniture originating from their city was selling abroad at auction houses for as high as six-digit figures and being reproduced for consumers wanting to own Jeanneret’s design sensibility.

As a result, importing Pierre Jeanneret originals from Chandigarh has now become difficult or impossible and the same dealers who purchased the pieces in large quantities earlier on control the market for what remains in the West. Since demand is high, and quantities are limited, the prices for Jeanneret’s Chandigarh furniture continue to soar on the secondary market. Meanwhile, Pierre Jeanneret is once again being recognized internationally through this renewed interest in his contributions to the city that finally set him apart from his cousin.

Story by Rupi Sood

Chandigarh was such an extraordinarily poetic but also major, major project with intellectual, social, political components.

François Laffanour, Galerie Downtown (Paris, France)